Faces in the clouds

In literature and popular fiction, our tendency to merge automation and personality is older than electrification or science fiction. The title character in Goethe’s poem “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” (1797) uses magic to animate a mop and streamline his chores, but the mop develops a mind of its own and unintended consequences follow.

A lot of robot stories are versions of “Pinocchio” or the Pygmalion myth. Boy makes girl. Boy wants girl as a companion. Girl/puppet/AI conveniently wants exactly what boy/creator wants (or she doesn’t).

When you dig into “anthropomorphism” online, you quickly get to Stewart Guthrie, an anthropologist who says our tendency “to see faces in the clouds … punishments in accidents, or purpose behind illness” arose as a way of “dealing with uncertainty in perception.”1 Guthrie’s familiarity thesis, as it’s come to be known, says that we anthropomorphize things we don’t understand because it is comforting to think of unfamiliar things as similar to ourselves.

We could be reductive and say that our impulse to grant AI human agency is simply narcissism. We anthropomorphize not as a means to greater understanding, but as an end in itself. Anything that isn’t me really is me.

My own wiring makes me think in terms of communication and relationship. Whether it’s Geppetto and Pinocchio, Captain Picard and Data, or Theodore and Samantha in “Her,” the longing to connect feels fundamental to these anthropomorphic stories. Automation is a romance, even if things go wrong.

The possibility of talking to the machine is so enthralling that we cannot help but think in stories instead of in functional specifications. We fell into the current AI craze because ChatGPT-3 delivered text that sounded so much like human discourse that the feeling that someone is there was virtually impossible to avoid.

To maintain the cognitive dissonance that what feels like relating is an illusion demands extraordinary discipline, especially when most people don’t know the difference between AI, ML, LLMs, bots, and algorithms in the first place.

Kubrick’s 2001 is based in part on the Arthur C. Clarke story “Childhood’s End.” How can we evolve our own AI narratives from anthropomorphic romances to more complicated grown-up stories about what we wish and how we actually live?

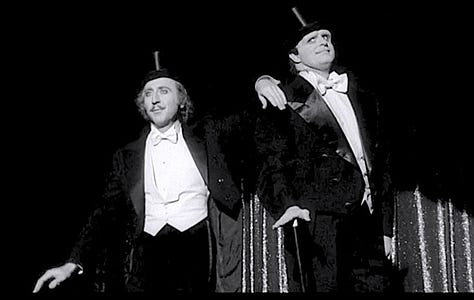

Fantasia (1940)/The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (1797), Desk Set (1954), The Jetsons (1964), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Young Frankenstein (1974)/Frankenstein (1818), Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987), A.I. (2001), Her (2013), Avengers: Infinity War (2018)

Afterthoughts and disclaimers:

My ideas about how we imagine intelligent machines are steeped in a sci-fi history and personal history dominated by male storytellers. Gene Roddenberry, Frank Herbert and Spike Jonze loom larger in my imagination of AI than, say, Madeleine L’Engle and Ursula K. LeGuin, who I also read (and who both had a lot to say about the tension between advancement and existential threat).

Given that history of speculative fiction (and the history of Silicon Valley), it’s significant how many of today’s essential AI critics are women and women of color: Professor Emily Bender, Timnit Gebru and Deborah Raji, to name three who dominate my own learning process. Professor Bender’s clarion call against “blurring — bullshitting — what’s human and what’s not” ought to guide the entire AI inquiry.

An analysis of AI discourse based on the impulse to anthropomorphize is still just one among several possible ways to interrogate AI narratives. Our longstanding atomic nightmares, industrial dystopias, and fables of tech hubris all offer other ways into the question.

I was going to talk about “animism” and the history of imbuing non-human phenomena with sentience or spirit, but when I saw that the term first appeared in analyses of “primitive cultures” by a British anthropologist in the late 1880s, its value as a lens seemed less certain.

From a review of Guthrie’s Faces in the Clouds (1993) by William B. Drees in Isis: A Journal of the History of Science Society, 2000 91:1.